Opinion

Building and busting trust in humanitarian action

Nick van Praag • 9 December 2019

Several years ago in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp I witnessed a refugee official glad-handing Syrian refugees as he went about his daily rounds, the very picture, to me at least, of a trusting relationship. Later, back in Amman, I described the scene to a Syrian refugee friend. Talking is good, she told me, but it’s not enough. Amidst the skewed power dynamics in the humanitarian space, there’s more to relations between aid providers and recipients than meets the eye.

The Zaartari episode came to mind when we were asked to prepare a background paper on the drivers of trust in humanitarian action for last December’s International Conference of the Red Cross / Red Crescent. My colleagues Emma Pritchard and Louise Maranda found some clues in interviews conducted with 7,000 people across seven countries in Ground Truth Solutions’ Humanitarian Voice Index.

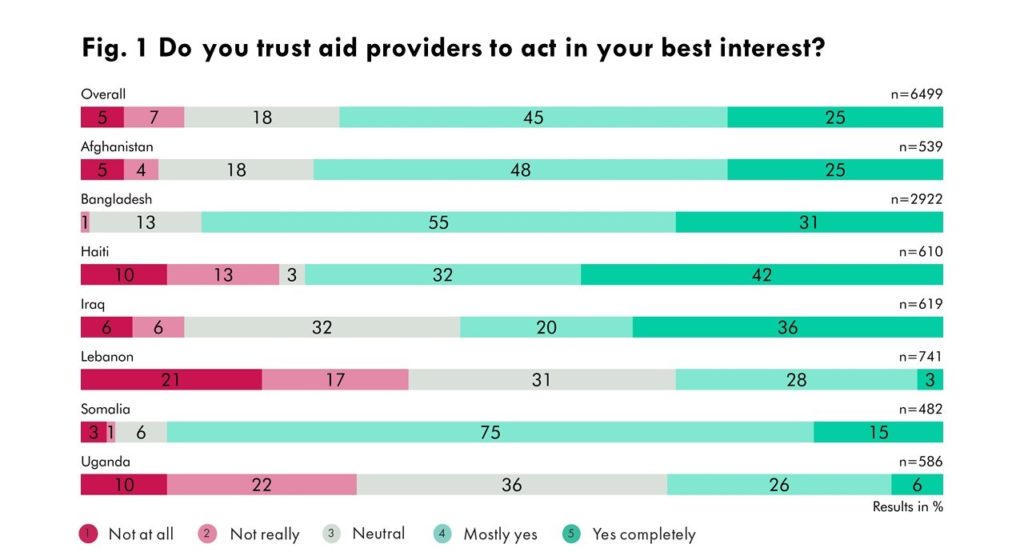

When affected people were asked whether they trusted aid providers to act in their best interests, the response was positive. Across our multi-country sample, some 70 percent of respondents consistently said they trusted aid providers (see Fig. 1).

On the face of it, this seems encouraging except that when the same people were asked about the quality of aid received, the accountability of aid providers, and their long-term prospects, the responses were a lot less positive. One might explain away this seeming contradiction as the result of what survey experts describe as “courtesy bias.” Politeness may indeed play a part in the way people respond, but we were never completely satisfied with this interpretation. Revisiting the data and reviewing theories of trust, another explanation suggests itself: one that stems from the vulnerability of affected people caught up in the unequal power dynamics of the humanitarian space.

Jack Barbalet, in his study on trust and its consequences, argues that trust between people requires vulnerability to the possibility that trust can be broken. The greater the power imbalance, the greater the vulnerability. Karen Cook, professor of sociology at Stanford University, argues that people affected by crisis compensate for this uncertainty by hoping they won’t be let down. In other words, what we thought was a question that probes the level of trust between aid providers and aid recipients may actually reflect a sense of hope rather than trust.

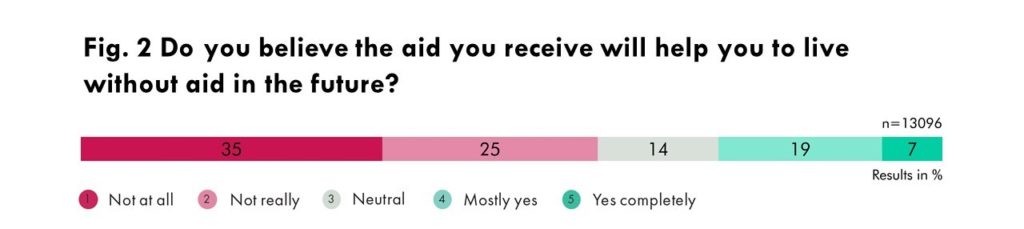

How, then, to measure trust in humanitarian action? Most people in crisis want, above all, to take back control of their lives. If standing on their own feet is at the top of their wish list, delivering on it is a good litmus test of trust in aid providers. To understand whether this is the case, we asked aid recipients whether they felt enabled by the aid they received to live without it in the future.

On this question, the responses were much less positive (see Fig. 2). More than 50 percent of respondents said that the actions of aid providers would not enable them to become self-reliant in the future.

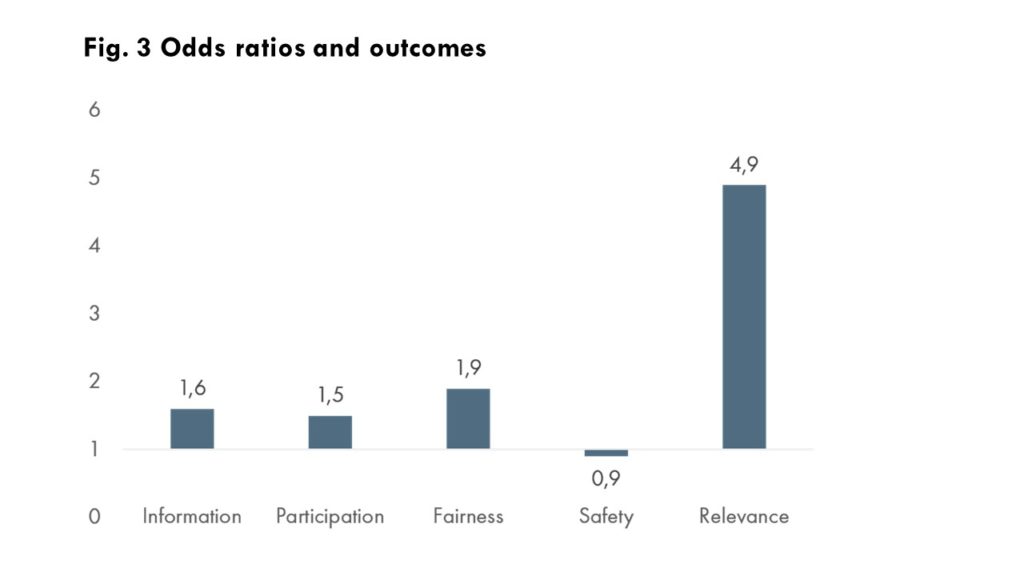

To determine what might influence affected people’s views on achieving the self-reliance they desire, we looked at the way they responded to questions about their access to information, participation in decision-making, fairness of aid provision, physical safety, and the relevance of aid in meeting people’s priority needs – all core themes of the humanitarian reform agenda.

We then looked at the odds ratios to measure the associations between people’s responses on self-reliance and those core themes. Associations are stronger for some issues than others (see Fig. 3). People who say they have the information they need are one-and-a-half times more likely to believe they will be able live without aid in the future. The same odds hold for the extent to which they consider themselves able to participate in decisions that affect them. While the odds ratios are positive, only half the respondents actually said they felt informed about the aid available to them.

The fairness of aid provision is also a factor strongly associated with self-reliance. People who believe aid goes to those who need it most are nearly twice as likely to feel they will be able to live without aid in the future. All well and good except that only 43 percent of respondents across the seven-country sample said that aid was provided equitably, and considerably fewer believed they were able to participate in decisions that influenced their lives. In practice, therefore, the relatively strong associations between fairness of aid provision and people’s sense that they will be able to live without aid in the future does not necessarily mean that all is good on the ground.

In contrast, responses to questions about safety show little relationship to people’s belief in positive outcomes. Somalia is the exception. People there were three times as likely to feel that they would be able to live without aid in the future if they were safe. But overall, the odds ratios between self-reliance and safety are low, meaning there is little association between a sense of safety and future self-reliance – perhaps because safety is influenced by many factors over which aid providers have little control.

What jumps out of the analysis is the powerful association between the way people see the relevance of aid in meeting their priority needs today and their optimism about self-reliance in the future. People who feel that aid covers their current needs are nearly five times as likely to consider it will help them to live without aid in the future.

With humanitarian aid focusing primarily on immediate and urgent needs, there is no obvious link to self-reliance. However, the data suggests that when affected people trust an aid provider’s ability to meet short-term needs, they are more likely to trust their ability to support positive outcomes in the long term. The correlation is striking but – with 75 percent of the 7,000 people we interviewed saying aid did not meet their most pressing needs -- we still are a long way from harnessing the power of this association.

If, like a brand, trust is a promise kept, the data suggests that giving people more chance to participate in decision-making, enhancing information provision, and improving their perceptions of the fairness of aid could all play a part in improving the quality of relations between the aid providers and those on the receiving end. The main lesson from the data, however, is that the biggest pay-off in terms of building trust is by meeting their priority needs. Action, not just words. This is as true in Zaatari as it is in other humanitarian settings.