Opinion

Time to act on what affected people tell us about humanitarian hotlines

Nick van Praag • 6 May 2019

In the wake of Cyclone Idai in Mozambique, many relief agencies rushed to set up hotlines, offering affected people a direct link to those tasked with assisting them. Trying to capture the concerns and suggestions of affected communities is important in any humanitarian emergency, but hotlines alone are not the answer in ensuring their voices are heard and heeded.

From the close to 5,000 interviews that we conducted with affected people across seven major humanitarian operations in 2018, we found that just over half of respondents know how to make suggestions or complaints to agencies. When asked how they would like to do so, most opt for face-to-face communication, preferably through their own community representatives, rather than by phone.

Despite concerns about the shortcomings of hotlines – see my earlier post on this topic – a search of ALNAP’s evaluations database reveals that there are no studies specifically dedicated to gauging their effectiveness. Lack of evidence has not, however, hindered their spread. Often one emergency response will have multiple hotlines; after Cyclone Idai, several relief agencies set up new hotlines on top of those already there. “A plethora of hotlines creates confusion and inevitably undermines their effectiveness,” says Alexandra Sicotte-Levesque, head of community engagement at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

The focus in Mozambique is now shifting to consolidating multiple lines into a collective service, which is increasingly considered best practice. But common call centres face the challenge of ensuring follow-up on people's requests and concerns. When an operator does not have the information to provide an answer right away, referral to the appropriate agency or cluster is inevitably slow.

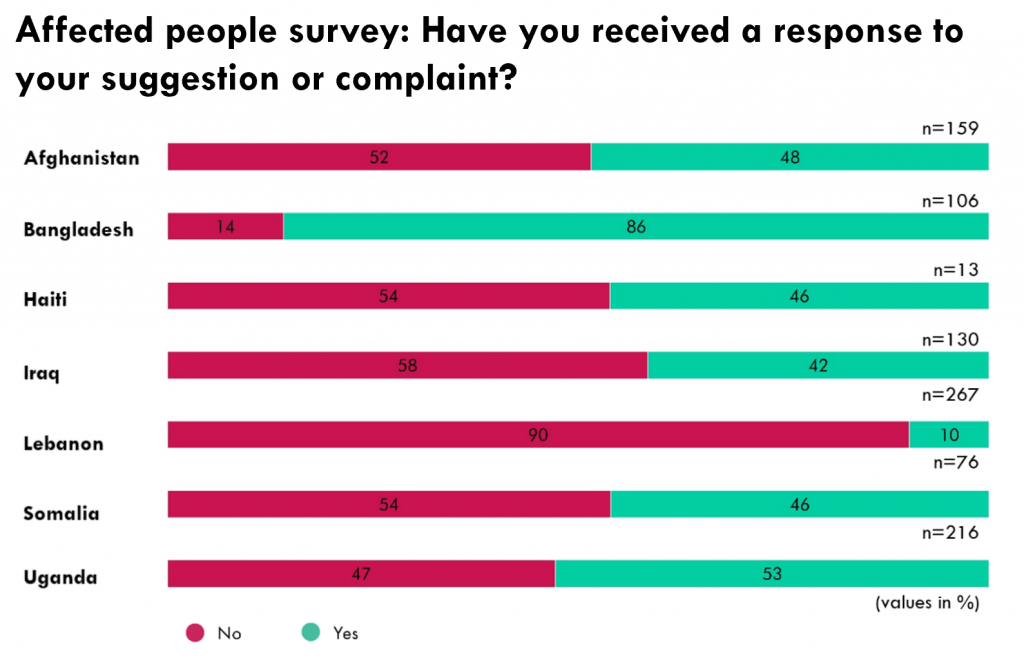

Significantly, our data shows that humanitarian staff tend to overestimate the effectiveness of existing complaints mechanisms, while affected people who have actually filed complaints or made suggestions are not so sure they will hear back.

The challenge goes beyond ensuring consistent referral and response. In Chad, only a third of respondents to a 2018 Ground Truth Solutions survey said they had access to a cell phone. With twice as many men saying they have cell phone access as women, hotlines risk reinforcing the gender gap. Additionally, few agencies in Chad have the capacity to interact effectively with callers in a country where over 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Language barriers are also a factor limiting the usefulness of hotlines for Rohyinga refugees in Bangladesh.

For Meg Sattler, an expert on accountability to affected people, the major problem with hotlines is their overstated role in ensuring accountability. “Having a hotline that can be called an ‘accountability mechanism’ ticks the community engagement box for aid agencies and donors alike. Although they may serve a purpose for people seeking information and registering complaints, it is irresponsible to equate them with accountability,” she says.

Hotlines can play a role in humanitarian emergencies, but only alongside other forms of community engagement. More effort must go into communicating with affected people, using channels they tell us they prefer, and proactively engaging with the broader affected community, rather than simply waiting for individuals to call in their concerns. Without a more comprehensive approach, hotlines will remain tokens rather than tools of accountability.