Opinion

Abuse, complaints and the trust deficit

Nick van Praag • 8 October 2018

A crisis of confidence has engulfed the humanitarian aid sector since revelations earlier this year of international staff in Haiti hiring sex workers after the 2010 earthquake.

The outcry has led Penny Mordaunt, Britain’s secretary of state for international development, to host an international conference in London on October 18 to agree on measures to prevent sexual exploitation and to ensure that such behaviour is less likely to happen in the future.

Beyond soul-searching and expressions of condemnation at the London conference, there will likely be a lot of talk about beefing up complaint mechanisms so that people who have experienced abuse can raise the alarm and hold perpetrators to account. But this pre-supposes that such complaint mechanisms are fit for purpose – something that is far from assured in the conditions that prevail in many humanitarian operations, as our data shows.

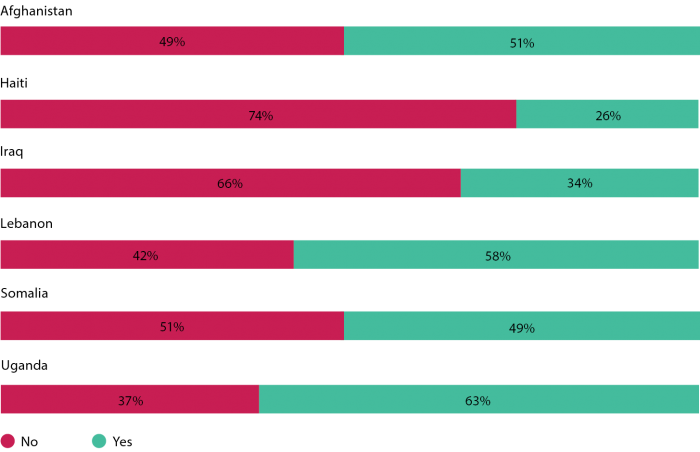

What we discovered in a six-country study with the OECD is that many people in humanitarian crises are unaware of how to make complaints, whether these relate to aid provision, abuse, or anything else. Furthermore, when asked whether they believe they would get a response if they did make a complaint, the majority say they doubt they’d hear back.

Do you know how to make suggesetions or complaints?

Our data also shows that hotlines are never the preferred channel to make complaints. People prefer face-to-face conversations, preferably one-on-one, with actors who are not directly associated with programme implementation. Not surprising, really, when they have no idea who is on the other end of a hotline or how a complaint would be handled.

It’s not just about affected people’s views of the relative merits of different feedback mechanisms. Central to whether anyone will be proactive enough to make a complaint is the broader issue of trust between benefactors and beneficiaries, which determines whether people will actually avail themselves of such mechanisms.

Our data on a set of issues that relate to trust is troubling. Although most people surveyed in our six-country study say they feel respected and relatively safe, they don’t feel aid is provided fairly. Moreover, they tend not to feel empowered and they don’t believe they get a chance to participate in decisions that affect their lives.

Across the six countries we see a positive correlation between the way people respond to questions on participation and the way they respond to knowledge of complaint mechanisms. So, the more marginalised and alienated people feel, the less likely they are to trust complaint mechanisms.

It’s time to go beyond the mechanics of making complaints. First, aid agencies need to proactively build and nurture trust through an ongoing dialogue with affected communities. They must show that feedback will lead to real change, and that they take the opinions of those they are serving seriously. Only when the population feels sufficiently empowered will they start making complaints and raising concerns. And when those complaints do come in, effective referral systems need to be in place, ensuring concerns are dealt with swiftly and appropriately.

Finally, even where there is trust between providers of aid and people affected by crisis, third parties have a role to play. In most situations, safeguarding mechanisms expect people to complain to the same organisation whose staff members may have abused them. Some donors already rely on third parties to help with their regular programme monitoring; the same principle should be extended to safeguarding.

As humanitarian leaders prepare for the London meeting, they must look beyond self-policing and complaint systems. Safeguarding by aid agencies can only work where it is embedded in a fabric of trust and participation, supported by independent, external actors.